Jewish Holy Books

This is by no means an exhaustive list of all the books which Jews consider to be sacred, but I hope it will prove a useful survey of many which hold a central place of importance in Jewish tradition and history.

• What is in the "Jewish Bible"?

• Torah Readings for Shabbat morning (Shacharit)

• Torah Readings for Shabbat afternoon (Minchah)

• Haftarah Readings

• Psalms

• Prayerbook

• Talmud: Mishnah and Gemara

• Midrash

• Law Codes

• Responsa Literature

What is in the "Jewish Bible"?

The Jewish bible goes by many names, including "The Hebrew Scriptures," "The Hebrew Bible," and "The Old Testament" (a term employed by some Christians, but not accepted by Jews). We call it TANAKH, which is a Hebrew acronym for the three sections it contains: Torah (Pentateuch), Nevi'im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). The Tanakh contains 39 books.

Torah Readings

The Torah is read weekly in synagogues on Shabbat morning, as well as on Mondays and Thursdays, and on holy days and festivals. It is divided into parshiot (portions) which are read consecutively, each week, throughout the year. On certain days, because of festivals or an upcoming holiday, special readings supplant the weekly reading. The cycle then recommences the following week. We begin reading the Torah, from the first parshah, on Simchat Torah, and finish the following Simchat Torah. Some synagogues employ the Triennial Cycle, which originated in Palestine. Each Torah portion is divided into three sections: the first section of each is read during the week for that designated Torah portion during the first year of the three-year cycle; the second section of each Torah portion is read during the second year of the cycle; and the third section of each Torah portion is read during the third year of the cycle. In this way, although part of each Torah portion is read within one calendar year, it actually takes three years to complete the reading of the entire Torah. There are many variations of the Triennial Cycle in use.

The Torah is read weekly in synagogues on Shabbat morning, as well as on Mondays and Thursdays, and on holy days and festivals. It is divided into parshiot (portions) which are read consecutively, each week, throughout the year. On certain days, because of festivals or an upcoming holiday, special readings supplant the weekly reading. The cycle then recommences the following week. We begin reading the Torah, from the first parshah, on Simchat Torah, and finish the following Simchat Torah. Some synagogues employ the Triennial Cycle, which originated in Palestine. Each Torah portion is divided into three sections: the first section of each is read during the week for that designated Torah portion during the first year of the three-year cycle; the second section of each Torah portion is read during the second year of the cycle; and the third section of each Torah portion is read during the third year of the cycle. In this way, although part of each Torah portion is read within one calendar year, it actually takes three years to complete the reading of the entire Torah. There are many variations of the Triennial Cycle in use.

Haftarah Readings

Each Shabbat, and on festivals and holy days, a passage from one of the books of the Prophets (Nevi'im) is read following the Torah reading. This is called the Haftarah portion, from the root [pey- tet- reish] meaning "complete" or "finish." The passages designated as Haftarah portions "complete" the reading of the Torah. They are related, either thematically or tangentially, to the Torah portion of the week. Unlike the Torah reading, which progresses through the Torah in an orderly and systematic fashion, the Haftarot readings are pegged only to particular Torah portions. In a calendar year, only a fraction of the material in the books of the prophets is read.

Prayerbook: The Siddur

The siddur (prayerbook) derives its name from the Hebrew word "seder" meaning "order." The prayers are arranged in a specific order, which was developed in the early centuries of the Common Era and has been expanded through the ages. Most siddurim (plural of siddur) contain the prayers for evening (Ma'ariv), morning (Shacharit), and afternoon (Minchah) prayer services for Shabbat, holy days, and weekdays. A machzor is a prayerbook for the High Holy Days (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur). The prayerbook, perhaps more than any other single Jewish book, expresses the beliefs, hopes, and yearnings of the Jewish people for a world ruled by justice and compassion. It provides a unique insight into Jewish thinking and Jewish values.

The siddur (prayerbook) derives its name from the Hebrew word "seder" meaning "order." The prayers are arranged in a specific order, which was developed in the early centuries of the Common Era and has been expanded through the ages. Most siddurim (plural of siddur) contain the prayers for evening (Ma'ariv), morning (Shacharit), and afternoon (Minchah) prayer services for Shabbat, holy days, and weekdays. A machzor is a prayerbook for the High Holy Days (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur). The prayerbook, perhaps more than any other single Jewish book, expresses the beliefs, hopes, and yearnings of the Jewish people for a world ruled by justice and compassion. It provides a unique insight into Jewish thinking and Jewish values.

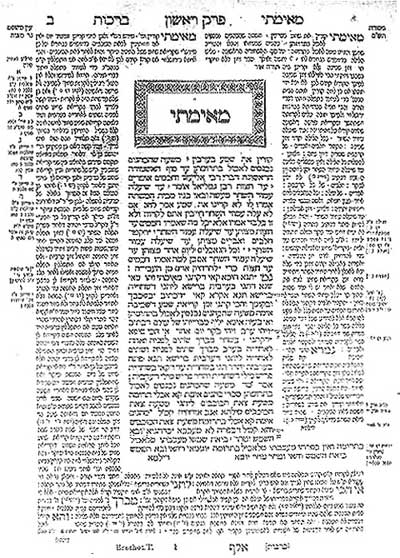

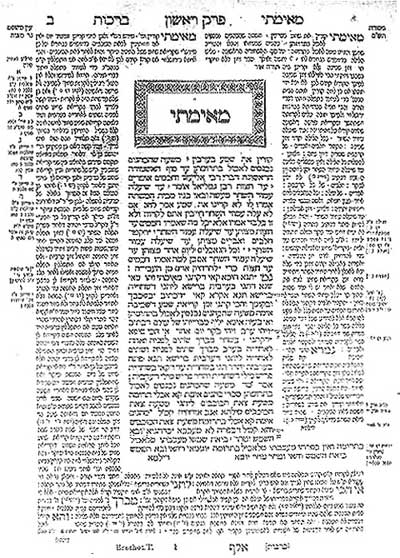

Talmud: Mishnah and Gemara

Tradition holds that Moses received two Torahs on Mount Sinai. One, known as the Written Torah, contains the Five Books of Moses known as the Pentateuch. The second, known as the Oral Torah, contains the Mishnah (codified by Judah HaNasi at the end of the second century of the Common Era) and the Gemara (a discussion of the Mishnah which took place in the academies of Babylonia between the years 200 and 600 CE). In truth, there are two Talmuds: one was written in Babylonia and the other in Palestine. The former is known as the Talmud Bavli, and the latter is known as the Talmud Yerushalmi. When people speak of "the Talmud," they are referring to the Babylonian Talmud.

Tradition holds that Moses received two Torahs on Mount Sinai. One, known as the Written Torah, contains the Five Books of Moses known as the Pentateuch. The second, known as the Oral Torah, contains the Mishnah (codified by Judah HaNasi at the end of the second century of the Common Era) and the Gemara (a discussion of the Mishnah which took place in the academies of Babylonia between the years 200 and 600 CE). In truth, there are two Talmuds: one was written in Babylonia and the other in Palestine. The former is known as the Talmud Bavli, and the latter is known as the Talmud Yerushalmi. When people speak of "the Talmud," they are referring to the Babylonian Talmud.

As Israel encountered the cultures of the west, primarily Hellenism and the Roman Empire, and as the population grew and became increasingly urbanized, new situations arose which the agriculturally-oriented Torah did not address. New legislation, and even more, new approaches to applying the Torah to contemporary life, were needed, and the Pharisees responded with the traditions that eventually were incorporated in the Mishnah, a work that is both legalistic (codifying the practice current at the end of the second century, CE) as well as descriptive (preserving descriptions of how Jewish life and ritual were lived in the Second Temple Period). These laws and traditions, learned and transmitted independently of the biblical text, were passed on orally for many generations. In the generation of Judah HaNasi (Judah the Prince), however, the number of knowledgeable Jews seems to have dropped precipitously (no doubt due to the devastating losses suffered during the Revolt of 69/70 CE and the Bar Kochba Rebellion of 135 CE) inspiring Judah HaNasi to break with the long-held oral tradition and commit the teachings in his possession to writing. The Mishnah, as it has come down to us, was written and closed by Judah HaNasi, the leading scholar and religious authority of his generation, around the year 200 CE., thus making it possible to transmit Jewish learning despite a dearth of rabbis and sages in his generation. The Mishnah is divided into six sections (called sedarim), which are further subdivided into 63 tractates; it addresses the full spectrum of issues of Jewish life at the time. It is organized by the general rubrics of Jewish life, making it possible for one to "look up" laws on specific issues. It was carried to Babylonia, where Jewish life and scholarship flourished following the Roman destruction, and for the next millennium, where it formed the basis of spirited debates and discussions in the academies there, primarily those of Sura and Pumpedita. The edited and redacted transcript of those discussions and dissertations on the Mishnah is called the Gemara, and together, Mishnah and Gemara comprise the Talmud. (The one exception to this is the tractate Avot, which contains no Gemara.) In its printed form, it is combined with many commentaries wrapped around the central core of text, with even more commentaries in the back of each of its twenty volumes.

The Talmud serves as the core of rabbinic tradition. Its approach to Jewish legal issues makes clear that as much as performing mitzvot (commandments) is important to living a full Jewish life, study is as well. In more than one place, issues so esoteric as to be entirely unapplicable are discussed in detail and at great length and it is pointed out that the purpose of the study is for its own sake, and that study brings its own reward.

The Mishnah is written in a terse and simple style of Hebrew. Most of the Gemara is written in Aramaic, though it contains passages in Hebrew, as well. The Gemara is often divided into two styles: Halakhah and Aggadah. Halakhah is legalistic material and Aggadah is legend. They are interwoven into a seamless whole, as are obligation and story in our own lives.

The six orders of the Mishnah and Talmud are:

ORDER |

CONTENTS |

| Zera'im (Seeds) |

Contains the agricultural rules of ancient Palestine, especially the rules concerning produce which was brought to the Temple in Jerusalem as an offering as well as the laws and traditions pertaining to blessings which are recited over produce and on other occasions, and prayer (which came to be the substitute for sacrifices in the service of God). |

| Mo'ed (Holy Days) |

Contains laws of Passover, Purim, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot and Shavuot. |

| Nezikin (Damages) |

Jewish civil and criminal law. |

| Nashim (Women) |

Contains laws and discusses issues pertaining to women, specifically laws of marriage and divorce. |

| Kodashim (Holy Things) |

Contains the laws of sacrifices and ritual slaughter. |

| Taharot (Purities) |

Contains the laws of purity and impurity. |

Midrash

Midrash is a magnificent genre of homiletical literature which interprets and teaches Torah. Its roots go back more than two millennia, and it continues to be a vibrant way to interact and express the religious and spiritual meaning of our sacred texts. Classical collections of midrashim are often categorized into two types of midrashic material: Midrash Halakhah, which expounds upon the meaning of legalistic passages of the Torah, and Midrash Aggadah, which uses the text as a jumping off point for a sermon, and often employs a story or legend in making its point. This may be too narrow a categorization, however, because there are also ethical midrashim, philosophical midrashim, and mystical midrashim. The art of midrash continues today, as Jews study the source texts of our tradition, and interpret them for our lives, deriving new meaning and revelation from their unlimited depth.

Among the classical compilations of midrashim are:

Tannaitic midrashim (composed before 200 CE, and written between 200 and 400 CE). These midrashim are called tannaitic midrashim because they contain attributions to sages -- tannaim -- mentioned in the Mishnah; however, they were redacted by the amoraim.

• Mekhilta de-R. Ishmael (on Exodus)

• Sifra de-be Rav (on Leviticus)

• Sifre (on Numbers)

• Sifre (on Deuteronomy)

Homiletical midrashim (composed in the 4th and 5th centuries)

• Beraishit Rabbah (on Genesis)

• Vayikra Rabbah (on Leviticus)

• Devarim Rabbah (on Deuteronomy)

• Tanhuma (or: Yelamdanu)

Later midrashim (composed in the 6th and 7th centuries)

• Pesikta de Rav Kahana (for special sabbaths and festivals)

• Pesikta Rabbati

• Ruth Rabbah (on the Book of Ruth)

• Shir HaShirim Rabbah (on Song of Songs)

Law Codes

From the time Jews found themselves living in widely divergent cultures, there have been questions about the proper observance of traditional practices. The Mishnah, though organized by subject area, does not read like an encyclopedia of Jewish practice, and the Gemara even less so. The need to compile answers to questions of observance, and the influence of other cultures which produced such compilations in other religious traditions (most notably Islam) contributed to the writing of law codes in Judaism.

Jacob ben Asher (1270? - 1340) came to be known as the Baal Ha-Turim (Master of the Rows) because he wrote a law code called the Arba'ah Turim ("the Four Rows"). Jacob ben Asher accompanied his father from Germany to Toledo in 1303, settling in Spain during Spanish Jewry's Golden Age. He was intellectually brilliant, but frustrated with the kabbalah, which was a regular feature of Jewish life at the time. He criticized its faulty reasoning and varying opinions. As a result, he wrote a halakhic work which compiled the mitzvot and minhagim (customs) he considered incumbent upon individuals and the community. The Arba'ah Turim contains four sections: Orach Chayim (blessings, prayers, Shabbat, Festivals, fasts); Yoreh De'ah (ritual law, usury, idolatry, mourning); Even ha-Ezer (laws affecting women: marriage, divorce, chalitzah ketubah); and Choshen Mishpat (civil law and personal relationships. His rulings were based upon the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben maimon, or Moses Maimonides), though he opposed the Rambam on issues of faith and belief, and upon the teachings of his own father, Asher ben Yechiel.The Arba'ah Turim marks a new level of codification of halakhah. It was quickly accepted as authoritative throughout the Jewish world, and Joseph Caro, Moses Isserles and Hayyim Benevistie, among others, wrote commentaries on it.

One of the most important of the law codes was written by the Rambam (Moses Maimonides) a rabbinic scholar, philosopher, and physician, who lived in Egypt and Spain in the 12th century, and who also authored the Moreh Nevuchim ("Guide for the Perplexed"). His 14-volume work is called the Mishneh Torah ("a second Torah") and was written with the express intent that people would find the Torah and his text sufficient to answer all their halakhic questions. The Mishneh Torah is a compilation of the commandments of the Torah, rabbinic teachings from the Talmud, Maimonides' philosophical convictions, and his own interpretations of tradition. Throughout, he infuses his work with commentaries on Jewish law which, in and of themselves, make fascinating reading. The Mishneh Torah is a reflection of Sephardic laws and customs of its time.

The Shulkhan Arukh was compiled by the Sephardic rabbi Joseph Karo in the middle of the 14th century. At the same time, an Ashkenazic rabbi from Poland, Moses Isserles (known as the Rama), was in the midst of compiling his own code. The Shulkhan Arukh was published with both scholars' rulings, Karo's listed first, and Isserles' dissents and additions listed afterward. The Shulkhan Arukh is published in four volumes, paralleling the divisions of the Arba'ah Turim.

Responsa Literature

Although Jewish law is based on the Torah and Talmud, and codified in a number of law codes, it is fundamentally case law, and answers to specific situations not covered in the general law were traditionally decided by legal authorities knowledgeable in all of the above. When a new situation presented itself, one would approach a halakhic authority with a she-elah (question), who would study the question and all the relevant texts, and promulgate a teshuvah (response). There exists an extensive body of literature known as She'elot U'Teshuvot (Questions and Answers), also known as Responsa Literature, from every generation and many, many countries in which Jews have resided through the centuries. Today, each of the three major Jewish denominations (Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox) promulgate their own teshuvot. Issues explored by teshuvot are as diverse as people themselves. Throughout history, She-elot U'Teshuvot have functioned to help Jews deal with the exigencies of life in a manner that is consistent with Jewish values and tradition. Many today deal with the implications of modern technological advances on our lives.

In the Reform movement, responsa are published by the Central Conference of Reform Rabbis. Some are now available on-line through the internet. The teshuvot of the Reform Movement are advisory, rather than obligatory in a legal sense.

The Rabbinical Assembly's Committee on Jewish Law and Standards is authorized to decide questions of Jewish law for the Conservative Movement. Many of the committee's decisions represent a departure from Orthodox practice, in response to the contingencies of modern life.

Among Orthodox Jews, who have no central authority, there are a number of highly esteemed poskim (legal decisors), and a large body of published She-elot V'Teshuvot.

The Torah is read weekly in synagogues on Shabbat morning, as well as on Mondays and Thursdays, and on holy days and festivals. It is divided into parshiot (portions) which are read consecutively, each week, throughout the year. On certain days, because of festivals or an upcoming holiday, special readings supplant the weekly reading. The cycle then recommences the following week. We begin reading the Torah, from the first parshah, on Simchat Torah, and finish the following Simchat Torah. Some synagogues employ the Triennial Cycle, which originated in Palestine. Each Torah portion is divided into three sections: the first section of each is read during the week for that designated Torah portion during the first year of the three-year cycle; the second section of each Torah portion is read during the second year of the cycle; and the third section of each Torah portion is read during the third year of the cycle. In this way, although part of each Torah portion is read within one calendar year, it actually takes three years to complete the reading of the entire Torah. There are many variations of the Triennial Cycle in use.

The Torah is read weekly in synagogues on Shabbat morning, as well as on Mondays and Thursdays, and on holy days and festivals. It is divided into parshiot (portions) which are read consecutively, each week, throughout the year. On certain days, because of festivals or an upcoming holiday, special readings supplant the weekly reading. The cycle then recommences the following week. We begin reading the Torah, from the first parshah, on Simchat Torah, and finish the following Simchat Torah. Some synagogues employ the Triennial Cycle, which originated in Palestine. Each Torah portion is divided into three sections: the first section of each is read during the week for that designated Torah portion during the first year of the three-year cycle; the second section of each Torah portion is read during the second year of the cycle; and the third section of each Torah portion is read during the third year of the cycle. In this way, although part of each Torah portion is read within one calendar year, it actually takes three years to complete the reading of the entire Torah. There are many variations of the Triennial Cycle in use. The siddur (prayerbook) derives its name from the Hebrew word "seder" meaning "order." The prayers are arranged in a specific order, which was developed in the early centuries of the Common Era and has been expanded through the ages. Most siddurim (plural of siddur) contain the prayers for evening (Ma'ariv), morning (Shacharit), and afternoon (Minchah) prayer services for Shabbat, holy days, and weekdays. A machzor is a prayerbook for the High Holy Days (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur). The prayerbook, perhaps more than any other single Jewish book, expresses the beliefs, hopes, and yearnings of the Jewish people for a world ruled by justice and compassion. It provides a unique insight into Jewish thinking and Jewish values.

The siddur (prayerbook) derives its name from the Hebrew word "seder" meaning "order." The prayers are arranged in a specific order, which was developed in the early centuries of the Common Era and has been expanded through the ages. Most siddurim (plural of siddur) contain the prayers for evening (Ma'ariv), morning (Shacharit), and afternoon (Minchah) prayer services for Shabbat, holy days, and weekdays. A machzor is a prayerbook for the High Holy Days (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur). The prayerbook, perhaps more than any other single Jewish book, expresses the beliefs, hopes, and yearnings of the Jewish people for a world ruled by justice and compassion. It provides a unique insight into Jewish thinking and Jewish values. Tradition holds that Moses received two Torahs on Mount Sinai. One, known as the Written Torah, contains the Five Books of Moses known as the Pentateuch. The second, known as the Oral Torah, contains the Mishnah (codified by Judah HaNasi at the end of the second century of the Common Era) and the Gemara (a discussion of the Mishnah which took place in the academies of Babylonia between the years 200 and 600 CE). In truth, there are two Talmuds: one was written in Babylonia and the other in Palestine. The former is known as the Talmud Bavli, and the latter is known as the Talmud Yerushalmi. When people speak of "the Talmud," they are referring to the Babylonian Talmud.

Tradition holds that Moses received two Torahs on Mount Sinai. One, known as the Written Torah, contains the Five Books of Moses known as the Pentateuch. The second, known as the Oral Torah, contains the Mishnah (codified by Judah HaNasi at the end of the second century of the Common Era) and the Gemara (a discussion of the Mishnah which took place in the academies of Babylonia between the years 200 and 600 CE). In truth, there are two Talmuds: one was written in Babylonia and the other in Palestine. The former is known as the Talmud Bavli, and the latter is known as the Talmud Yerushalmi. When people speak of "the Talmud," they are referring to the Babylonian Talmud.